Royalty Brasses

During the horse brass era many different designs adorned decorated harness and ranking high amongst those most sought by today’s collectors are ‘Royalty’ brasses. Production of the first of these is still a matter for debate. Some argue that brasses featuring the younger or ‘bun’ head of Queen Victoria actually date back to her coronation in 1837 but so far no proof has surfaced in support of this. Due to the untimely death of her beloved Prince Albert in 1861 no brasses were produced to celebrate her Silver Jubilee the following year but by the time of her Golden Jubilee in 1887 the Bristol, Birmingham and Walsall manufacturers were ready to take on the challenge of producing a huge range of brasses to help horsemen celebrate the event.

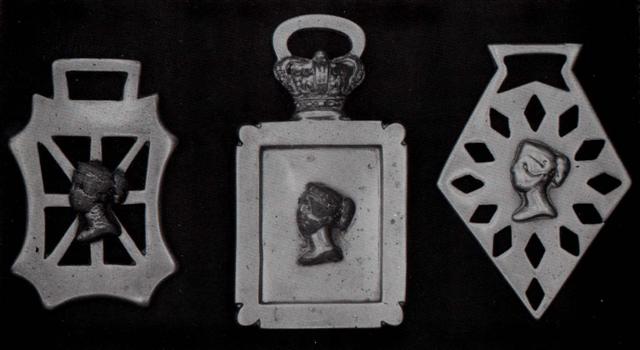

Queen Victoria 1837-1901

Below, three early ‘bun’ head types. The head is not actually as used on the coinage and postage stamps of the time but a very close approximation of it.

Edward VII. 1902-1911

After the death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 a new series of brasses was made to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII in 1902 and most of the large factories produced splendid examples (see Walsall and Birmimgham pattern books page) which include some of the patterns seen in the picture below.

Above, a small representative selection of brasses both cast and stamped, made for the coronation of Edward VII in 1902. The red, white and blue china centres are also typical of this period and were often worn with worsted rosettes or ribbon backing to achieve a more colourful display.

The matching pair of straps are loin or kidney straps. The hame-plate (bottom) is also typical of the period as is the splendidn swinger and face piece above. Very often Royalty brasses have survived in excellent condition with little or no evidence of harness wear. No doubt this is because they they were only occasionally used on show days and parades then either wrapped up and put away or displayed in the home. Some horsemen invested in several royalty brasses on new martingales while others would add a single brass to one of their existing decorated harness pieces. Where left on the harness and worn for many years many of the lead-filled applied crowns and sovereign’s heads were badly disfigured by lead bleed much in the way that RSPCA crests on merit badges were.

George V 1910-1936

For the coronation of George V in 1911 another fabulous crop of brasses was produced, a small selection from which is seen below.

Brasses from this period are ofter considered less numerous probably because by 1911 horse power in the major towns and cities was already in decline, yet some of the brasses produced during this era were extremely innovative and some of the best ever seen. This time portraits also included some of Queen Mary and the Prince of Wales, a theme repeated for the Silver Jubilee.

Above, four brasses made for the coronation of George V in 1911.

By the Silver Jubilee of George V in 1935, the heavy horse was in serious decline but despite this a few brasses were made to commemmorate the anniversary.

Edward VIII 1936 and George VI 1936 -1952

Coronation brasses of economic necessity were made and sold well before the event took place so that those prepared for King Edward VIII ‘s coronation had to be withdrawn after his abdication in December 1936 and hastily redesigned for King George VI. In consequence hardly any of the former appear with harness wear. Most of those produced for the coronation in 1937 were large portrait brasses showing King George VI, with some including Queen Elizabeth, the originals being of much better quality than the copies produced later.

Elizabeth II 1953-Present

In contrast with her late father’s coronation Queen Elizabeth II’s in 1953 saw huge numbers of brasses produced, many were of poor design and finish but they had been made mainly for the souvenir trade and not horse wear. By the Elizabethan Era the use of heavy horses had largely died out but in some of the towns and larger cities some short haulage work was still done by horses and the carters wishing to celebrate the coronation were duly provided for by some very well designed and finished brasses.

Above, a fine study of the Birkenhead Coronation Horse Parade in 1953, demonstrating just how many horses were still employed in the area in the early 1950s. Note the coal dray in the foreground which was the entry from Houldins Coal whose advertising proclaims ‘Houldin’s Coal is Grate Stuff’. One of many Coronation Parades taking place up and down the country, it followed a long tradition, offering a chance of public celebration, adverting and an oportunity to display their new coronation horse brasses.

Following the heritage revival of the heavy horse from the 1960s and the reintroduction of regional heavy horse societies hosting ploughing matches , horse parades and working drays together with the commercial use, in particular by breweries, the production of high quality Royalty comemorative brasses has steadily increased. This is particularly as a result of NHBS founder Terry Keegan and Ron Baldwin’s company ‘The Heavy Horse Enthusiast’, now run by Terry’s daughter and son-in-law, who have produced a steady flow of excellent brasses of all kinds since the 1970s amounting to many hundreds, and these provide the heavy horse man and the collector and with a continuous supply.

Below, 4 brasses commemorating the 1953 coronation

King Charles III

A selection of brasses to celebrate the coronation of King Charles.

Left: A fine display of Royalty brasses mounted on a purpose-made oak frame